His “racial attitudes, like his explorations of gender and class…(being) often contradictory, even violently conflicted at any given moment of his career”, it is difficult to define what stance Faulkner took towards racial issues in his native habitat of Mississippi, one of the more epitomized regions of the Deep South, which reinforced Jim Crow segregation laws. In the eyes of the law blacks were “separate but equal” from whites, legally on an equal level, but with African-Americans differentiated on the basis of skin colour, perceived and judged as being inferior to the Caucasian race. Disfranchisement became a prominent issue over the voting rights of blacks, as well as the education system which divided mere children over skin colour; increased lynchings ensued, with tensions broiling over economic hardships and the perceptions that immigration was taking jobs awat from the whites. Even in places where blacks and whites lived in close proximity, parents would be required to teach children about the mandated social distance between races, and the necessity of adhering to the racial status quo.

By “submerging himself in the mentality of the community where he was born”[2], Faulkner delves into his Southern heritage in exploring the racial tensions that defined the late-19th Century and early 20th century America. A late novel, Intruder in the Dust, explores the subject of racial domination through the story of a Negro who has embraced his role as an “Uncle Tom” figure to the extent that he is too submissive to even defend himself against a murder charge; in The Sound and the Fury, on the other hand, the black characters are decidedly less passive than this subservient figure. They are still servants—a family of them, indeed—but in many ways Faulkner presents characters who diametrically oppose the justifications for racial domination and symbolic categorization of the blacks in the South on account of their intelligence and wits, as well as forcing the reader to confront the realities of symbolic violence through the racism of characters like Jason Compson.

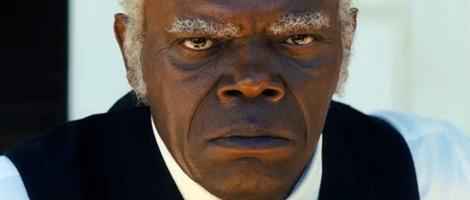

- Samuel L. Jackson's Stephen in Django Unchained is perhaps the most recent, well-known example of an Uncle Tom figure

A lowly character like Dilsey can still have power to dictate the actions of others—even Jason Compson, head of the household; her cries of “Hush, you, Jason!!” are sufficient to quiet down perhaps the most extrovertly violent character in the book. Through the character of Dilsey, the Negro housemaid who cares for Benjy with genuine love, but keeps her hands out of the more unsavoury matters of Jason and his philandering and petty crime, she can observe the Compson family without any sort of prejudice, and see “the full picture of the Compson household in all its incredible decrepitude” [4]. This seemingly passive role of the Negro servant is lampshaded by the constant repetition of the words “door” and “window” in the fourth chapter with predominantly views events from the viewpoint of Dilsey, but not through her narrative voice. She is still a lowly servant, and even the reins of the narrative voice cannot be given to her, but nevertheless her point of view provides the reader with more insightful, and less clouded, a judgement of the disintegration of the Compson family.

Victims of symbolic violence and prejudice like Benjy (prejudiced against by both family and complete strangers for being mentally underdeveloped), and Dilsey and her family, who are prejudiced against—though on what basis differs through the interpretations of the characters themselves. Dilsey’s grandson, Luster, sees himself being victimized by the Caucasian race as an individual—“That white man hard to get along with. You see him take my ball”, he bemoans at one point—and tells the white Benjy that he “’aint got nothing to moan about”. He reflects the attitude of a non-White in America experiencing the effects of racism in its basest form, racial domination, alongside the categorization of different races and ethnicities into different categories. Yet Luster is also, ironically, subverting the ethnic roles of the South by essentially having power over his own white master, Benjy; he orders him around, telling him to “Hush” at regular intervals, mocks Benjy by repeatedly uttering “Caddy” to provoke a reaction. Though he does occasionally find himself at the mercy of white characters—like Jason who holds in his hands money for Luster to go to a show and cruelly burns it—he is a character who Dilsey herself describes as having “sass” and is decidedly not submissive.

- From The Guardian: James Franco as Benjy Compson

After hearing this speech, Dilsey emotionally cries that she has “seed de first en de last”; the preacher’s act of defiance against the symbolic oppression of the Negro as a passive figure has opened up Dilsey’s eyes to a future in which blacks can finally transcend fickle racial profiling and categorization, and all men and women, regardless of colour or creed, can be all seen as the children of God. They do not contribute to symbolic violence against their own race because they do not adhere to stereotypes, they do not internalize prejudice against one another and most certainly do not participate in “accepting and supporting the terms of their own domination”[13]. Their “willingness” to serve their White masters is a pragmatic choice, a “patient willingness to endure is another mask they assume in order to find their way through a hostile world”[14]

[1]JOHN JEREMIAH SULLIVAN, How William Faulkner Tackled Race — and Freed the South From Itself, The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/01/magazine/how-william-faulkner-tackled-race-and-freed-the-south-from-itself.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[2] Edmund Wilson, William Faulkner’s Reply to the Civil-Rights Program, Faulkner: A Collection of Critical Essays, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1966, p. 219

[3] Robert Penn Warren, Faulkner: The South, the Negro, and Time, Faulkner: A Collection of Critical Essays, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1966, p. 256

[4] Robert A. Martin. ‘The Words of “The Sound and the Fury”’. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, fall 1999

[5] John Jackson Jr., Harlemworld: Doing Race and Class in Contemporary Black America, Chicago, Il, University of Chicago Press, p. 171, 188

[6] Peter Swiggart, “Moral and Temporal Order in The Sound and the Fury”, Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, spring 1953

[7] Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer, What is Racial Domination, W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Du Bois Review, 6:2, 2009, p.247

[8] Arthur F. Kinney, "Faulkner and Racism," Connotations 3.3 (1993-94)

No comments:

Post a Comment